It was August 24, 1814, two years into the War of 1812 ⧉. The fledgling United States, formed just 31 years earlier, was in great peril as they found themselves embroiled in a war with Great Britain, one of two great world powers of the time. Although the War of 1812 was caused by the actions of a militarily superior Great Britain, many in the young American republic believed the war was a foolhardy, self-destructive endeavor—an endeavor that was destined to fail…or was it?

After an embarrassing American loss at Bladensburg ⧉, Maryland, British troops entered Washington D.C ⧉. and set fire to the White House (then known as the ‘President’s House’), the unfinished Capitol building, the Library of Congress and the Treasury. After spending a night in the city, and enduring a ferocious, tornado-spawning hurricane ⧉, the British troops withdrew. As they left the city, they torched what remained of the Navy Yard, Treasury and the building that housed the State, War and Navy departments. As the British troops withdrew from the city and a new, larger force of American troops entered, two opposing attitudes prevailed. The burning of the American capital dealt a devastating blow to the morale of many, but equally powerful was the new sense of resolve and determination felt by others.

Doctor William Beanes

Dr. William Beanes ⧉ was born on January 24, 1749, in the small town of Croom, Maryland. After completing his public education, William decided he wanted to be a doctor. Because there were no formal medical schools to attend, William’s parents hired a doctor to teach him. When the Revolutionary war broke out, Dr. Beanes volunteered and served as a physician at the hospital in Philadelphia. Beanes later attended to many soldiers on the front lines and through the devastating winter at Valley Forge.

On August 22, 1814, some 31 years after the end of the Revolutionary War, the British army, commanded this time by Major General Robert Ross ⧉, once again marched on U.S. Soil. Their goal this time was to break the will of young republic by the capturing and destroying Washington, D.C. As evening drew closer, General Ross and his 4,500 troops sought a place to spend the night and the house and land of Dr. William Beanes was commandeered. Beanes was a gracious host to the British and the next day, when the troops resumed their march, they left believing they had found an ally who was sympathetic to their cause.

On August 22, 1814, some 31 years after the end of the Revolutionary War, the British army, commanded this time by Major General Robert Ross ⧉, once again marched on U.S. Soil. Their goal this time was to break the will of young republic by the capturing and destroying Washington, D.C. As evening drew closer, General Ross and his 4,500 troops sought a place to spend the night and the house and land of Dr. William Beanes was commandeered. Beanes was a gracious host to the British and the next day, when the troops resumed their march, they left believing they had found an ally who was sympathetic to their cause.

Two days later, on August 24, 1814, General Ross and his 4,500 battle-hardened soldiers met the American General William Winder of and his 6,500 soldiers, most of which were poorly trained volunteers, at Bladensburg, Maryland. Despite their positional advantage and numerical superiority, the Americans suffered a humiliating defeat at the Battle of Bladensburg. However, General Ross, unable to provide logistical support for his troops, abandoned Washington D.C. and retraced his path from a few days earlier and passed through Upper Marlboro without stopping. Some of the fleeing troops, however, were not content with victory alone and fell behind the main column of troops and began to raid houses and loot farms as they went. Dr. Beanes, along with some other men from the town, rounded up these troublemakers and put them in a local jail. However, one of the prisoners escaped and made his way back to Nottingham, where General Ross was to join Admiral Cockburn of the Royal Navy. When Ross heard what had happened, he immediately sent soldiers to Upper Marlboro to demand the release of the prisoners and to arrest Dr. Beanes and his copatriots. Under threat of burning the town to the ground, the British soldiers were released, but Beanes and his friends were marched to Ross and Cockburn. Shortly after their arrival, Beanes’s copatriots, Governor Bowie, Dr. James Hill, and Philip Weems were released, but Ross refused to release the 65-year-old Beanes, under pretense that he was a spy.

This turn of events put the people of Upper Marlboro into a great panic. Dr. Beanes was a trusted and highly respected friend to many in the region. Upon hearing the news, Richard West, a close friend of Beanes, hastily traveled to Georgetown to discuss the events with his brother-in-law lawyer, Francis Scott Key.

Francis Scott Key

Francis Scott Key ⧉ was born on August 1, 1779, in Frederick, Maryland. His father, John Ross Key, was a lawyer and officer in the Continental Army. Francis attended St. John’s College in Annapolis, Maryland and studied law under his uncle Philip Barton Key ⧉. Though he briefly considered becoming an Episcopal priest, he continued his practice of law and eventually opened his own practice in Georgetown, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Key was in his early 30s when the United States declared war on Britain. Key strongly opposed the decision to go to war with Britain, but when he heard the news of what had befallen the city of Washington and the fate of his friend Dr. Beanes, he resolved to take action. With the encouragement of his brother-in-law Richard West ⧉, Key requested permission from President James Madison ⧉ to negotiate the release of Dr. Beanes. President Madison agreed with the request and assigned General John Mason, the Commissary General of Prisoners, to make arrangements for Colonel John Skinner ⧉, an accomplished negotiator in his own right, to accompany Key.

Key was in his early 30s when the United States declared war on Britain. Key strongly opposed the decision to go to war with Britain, but when he heard the news of what had befallen the city of Washington and the fate of his friend Dr. Beanes, he resolved to take action. With the encouragement of his brother-in-law Richard West ⧉, Key requested permission from President James Madison ⧉ to negotiate the release of Dr. Beanes. President Madison agreed with the request and assigned General John Mason, the Commissary General of Prisoners, to make arrangements for Colonel John Skinner ⧉, an accomplished negotiator in his own right, to accompany Key.

Key and Skinner hastily made their way to Baltimore to intercept the British fleet. On September 5, 1814, Colonel Skinner and Key sailed out, carrying a flag of truce, to find the British fleet. Once they found the fleet, they were welcomed aboard the British flagship HMS Tonnant, by General Ross and Admiral Cochrane. After producing some key letters and correspondence that indicated Dr. Beanes was not a spy, Beanes was granted freedom—under one condition.

Baltimore

By 1814, Baltimore, Maryland ⧉, was the third largest city in the United States. The city boasted one of the busiest harbors on the United States’ East coast with deep waters that could accommodate ships of any size and was home to major shipbuilding activity—a prime target for military invasion. Baltimore was also the home for a significant number of American privateers—private ships legally engaged in maritime warfare—or what the British considered as pirates. Just as British privateering “Sea Dogs ⧉” had aided the British monarchy against the Spanish, American privateers were taking a significant toll ⧉ on the British Royal Navy. Since many privateers were sailing from Baltimore, capturing Baltimore would likely solve the problem for the British.

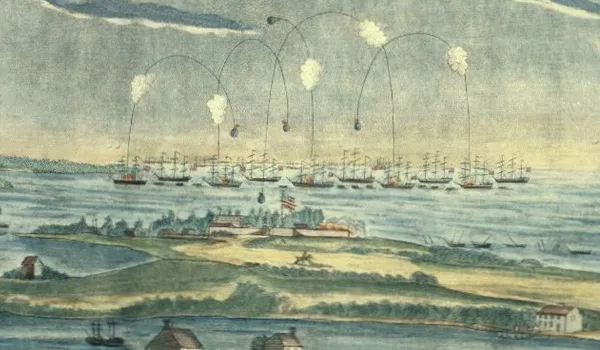

Shortly after capturing and burning Washington, the British fleet was headed towards Baltimore. A British victory at Baltimore would cause a major disruption of American trade, significantly reduce privateering, provide the British with a port close to Washington and significantly improve the likelihood of a British victory of the war. It was in the waters of the Chesapeake Bay, near Baltimore, that Francis Scott Key and Colonel John Skinner boarded the HMS Tonnant to negotiate the freedom of Dr. William Beanes. After securing the freedom of Dr. Beanes, the negotiators were informed that they could not leave and would have to stay onboard the Tonnant: they knew too much. To some degree plans had been revealed about the impending attack on Baltimore and the British were unwilling to have their plans revealed. For what seemed like ages, the Americans paced the deck of the Tonnant. Finally, they were released, under guard, to their own ship, where they were forced to continue waiting.

On September 12, 1814, British troops began their assault on Baltimore. The assault began when British and American

soldiers met at the Battle of North Point ⧉, followed

by a merciless bombardment of Fort McHenry. For 25 hours, the bombardment continued. Massive bomb

ships ⧉ with names like Devastation, Meteor, Volcano and Terror

launched 200lb bombs ⧉as high

as a mile, letting them explode in the air and rain fire on everything below or else crash down like massive flaming

boulders from the sky. Other ships, like the rocket ship HMS Erebus, launched hundreds of Congreve rockets, streaking

across the sky from distances over 3,000. It was a massive display of naval firepower that was heard in Philadelphia,

over 100 miles away. From their vantage point behind the British warships, Key, Skinner and Beanes watched helplessly,

fearing deep in their hearts that all was lost.

On September 12, 1814, British troops began their assault on Baltimore. The assault began when British and American

soldiers met at the Battle of North Point ⧉, followed

by a merciless bombardment of Fort McHenry. For 25 hours, the bombardment continued. Massive bomb

ships ⧉ with names like Devastation, Meteor, Volcano and Terror

launched 200lb bombs ⧉as high

as a mile, letting them explode in the air and rain fire on everything below or else crash down like massive flaming

boulders from the sky. Other ships, like the rocket ship HMS Erebus, launched hundreds of Congreve rockets, streaking

across the sky from distances over 3,000. It was a massive display of naval firepower that was heard in Philadelphia,

over 100 miles away. From their vantage point behind the British warships, Key, Skinner and Beanes watched helplessly,

fearing deep in their hearts that all was lost.

As the first gray streaks of sunlight began to light the sky on September 14, the battle was over. The fort’s guns went silent. The battle ridden storm flag that had flown during the battle was lowered. Had the British captured the fort? Then, ever so slowly, in a show of supreme defiance and triumph, Fort McHenry’s massive, 30’x42’ “Great Garrison Flag ⧉” was raised to the top of its 90 foot pole. The moment was not lost on Francis Scott Key and he soon began to write a poem entitled “Defense of Fort McHenry.” The words were set to music and eventually renamed “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

The Star-Spangled Banner

O say can you see, by the dawn’s early light,

What so proudly we hail’d at the twilight’s last gleaming,

Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight

O’er the ramparts we watch’d were so gallantly streaming?

And the rocket’s red glare, the bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there,

O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?

On the shore dimly seen through the mists of the deep

Where the foe’s haughty host in dread silence reposes,

What is that which the breeze, o’er the towering steep,

As it fitfully blows, half conceals, half discloses?

Now it catches the gleam of the morning’s first beam,

In full glory reflected now shines in the stream,

’Tis the star-spangled banner - O long may it wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave!

And where is that band who so vauntingly swore,

That the havoc of war and the battle’s confusion

A home and a Country should leave us no more?

Their blood has wash’d out their foul footstep’s pollution.

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave,

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

O thus be it ever when freemen shall stand

Between their lov’d home and the war’s desolation!

Blest with vict’ry and peace may the heav’n rescued land

Praise the power that hath made and preserv’d us a nation!

Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just,

And this be our motto - “In God is our trust,”

And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

(From this Smithsonian page ⧉)